- Originally posted on Prof. Katz's blog.

Last week reports emerged that the Government is considering a new copyright exception for political advertising. The reports suggested that the exception would permit the use of news content by political parties without authorization. While most of the media coverage of this story focused on the copyright issue and the phenomenon of attack ads, documents that Sun Media obtained from the CBC (under an Access to Information request) reveal an even more interesting and more important story, both politically and legally. These documents, offering a rare glimpse behind the scenes of Canada's major media organization, reveal a picture of a concerted action between the majority of Canada's news outlets, action that might run afoul the Competition Act.

The Government’s proposal—a proposal that seems to be unnecessary and misguided at once—might have been prompted by an agreement between the major electronic media organizations not to broadcast political ads that contain audio or video content appearing to come from news services owned by CBC/Radio Canada, CTV/Bellmedia, Global/Shaw, or City/Rogers. If what those documents appear to reveal is true, then the document that those documents reveal might be an illegal one, contrary to section 45 of the Competition Act. Thus, a story that broke as a minor (albeit important) news item about copyright reform, may turn out to be a much bigger story about possible violation of the Competition Act by Canada’s major media outlets.

The documents revealed by Sun Media (which was not a party to the agreement) show that in March 2014, a senior CBC official reached out to other media outlets, and together the members of that “consortium” (a term used in the correspondence) agreed that they would not broadcast political ads that incorporate content taken from the members' broadcasts. A letter dated April 22, 2014 had been promptly signed by senior official in each of those media organizations and was subsequently sent to all political parties. The broadcasters did not hide their agreement. Indeed, it was reported in the media, but it didn't receive the public attention that the Government's response would attract several months later.

In an email dated March 17, 2014, Jennifer McGuire, General Manager of CBC News and Centres, explained the background and motivation for reaching the agreement. “As you know”, she wrote (apparently to contacts in a competing media outlet, possibly Rogers), “we are already in pre-season of the federal election campaigning and, once again, we are seeing news content (in the case of the recent Justin Trudeau ads, CBC News content) being grabbed and used without permission and out of context in attack ads. This kind of activity will hit us all as the election activity heats up.” She continues to explain that “in the past broadcasters have argued individually against this activity legally using copyright infringement”, however, “our legal team is [now] confident that with the shifts in case law w.r.t fair dealing this might not be a successful route.”

Concluding that copyright could be invoked as grounds for not broadcasting the ads, the broadcasters decided to devise an alternative plan. “I have had preliminary conversations with CTV and with Global” wrote McGuire, “and we are all in agreement that this is an issue that needs to be addressed. We are exploring a joint position on this which is why I am reaching out to you. We would like to get to a place where we say to the parties, effective immediately, the networks will not air ads with unauthorized use of other broadcaster's news content. We believe this is the best route to see this activity stop.” And so they did. As mentioned earlier, a letter jointly singed by top official from those media organizations was subsequently distributed.

If what those documents reveal is true, then by agreeing among themselves not to broadcast such ads, the involved media organizations might have violated the core prohibition of the Competition Act. This is my analysis, based on those documents. Needless to say, no court has determined that such violation has occurred.

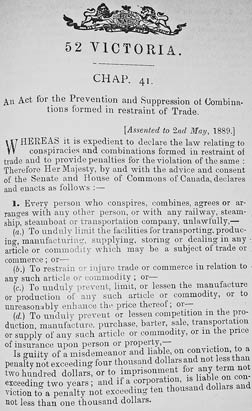

As the Competition Bureau explains, “Section 45 is the cornerstone cartel provision of the Competition Act. It makes it a criminal offence when two or more competitors or potential competitors conspire, agree or arrange to fix prices, allocate customers or markets, or restrict output of a product. This offence is known as a conspiracy, and is punishable by a fine of up to $25 million, or imprisonment for a term of up to 14 years, or both.” Such agreements are also actionable civilly, for example, by their victims. Alternatively, the Commissioner of Competition might pursue civil action against such agreement under section 90.1.

Behind the somewhat technical legal terms lies a simple important principle: The essence of free competition is that competitors make the relevant decisions pertaining to their business independently of each other. Competitors are supposed to decide what to produce, whom to deal with, what prices to charge, etc. each on its own, not in agreement with each other.

As a matter of competition law, the issue of “political attack ads: good or bad” is beside the point. Equally irrelevant is the question of whether copyright law requires advertisers to seek a broadcaster permission before an excerpt from a TV program can be used in a political ad. The Competition Act was enacted to ensure that competitors compete with each other rather than coordinate their behaviour. The CBC (or any other media organization) might think that attack ads are in bad taste, or harmful to the political process, or that its viewers don’t like them, or it might object to them on whatever other reason, and to the extent that it is under no legal obligation to broadcast them (for the purpose of this post I assume that no such obligation exists, though this is an oversimplification) then the CBC may decide not to broadcast them. The same goes for any other broadcaster, which is free to decide the content of its broadcasts for itself.

As a matter of competition law, as long as each media organization makes its own independent decision there’s usually no issue, even if they all end up doing and choosing the same thing (competitors often offer the same or similar products if this is what most consumers prefer). What they cannot do is agree collectively what to broadcast or not. For the purposes of the Competition Act, competitors are not allowed to decide together what to produce, or whom to deal with, just as they’re not allowed to agree on what would be the price that each of them charges for ads. The essence of competition is that competitors make those decisions on their own, not in concert with each other.

Likewise, a broadcaster might object to the use of footage from its programs in political advertising, and to the extent that it has full discretion on what to broadcast it can refuse to broadcast those ads regardless of whether the advertiser needs permission to use the footage as a matter of copyright law. If CBC (or any individual broadcaster) is concerned that an ad containing material from another network might expose it to potential copyright liability then it might refuse to broadcast the ad (or ask the adviser to indemnify it in case it is found liable). But this is not the case, because CBC’s legal department concluded that there isn’t likely to be any copyright issue (and most competent counsel would reach a similar conclusion). The broadcaster might still refuse to broadcast the ad, but other media outlets might then broadcast it, in which case the refusing broadcaster might lose the advertising money and its competitors might gain. Competitors don't like it when their rivals may pick up what they leave out, but this is exactly the kind of market discipline that the Competition Act is designed to protect, and the outcome that the media organization might have sought to avoid by agreeing that none of them would broadcast such ads.

Some may wonder if it matters whether the decision to enter into such agreement had been motivated by a belief that attack ads are harmful or distasteful, or by the broadcasters’ conviction that the Copyright Act should require political advertisers to seek their permission before using footage from broadcasts. The answer is: not really. Even if there is no direct profit motivation for entering into such agreement (and as I’ve speculated above, the fear of losing advertising revenue might have motivated the agreement, so this might not even be an example of an agreement divorced from any profit motive), collusive agreements between competitors are still generally unlawful.

Attack ads may be distasteful, or even according to some views harmful to the political process, but they are not illegal. Likewise, using excerpts of content from their own programs may be annoying for some broadcasters, but as even some of the broadcasters’ legal advisers agree, the Copyright Act does not prohibit that. If the broadcasters aren’t happy with this state of the law it is open to them to convince Parliament to change the law (within the bounds permissible for such limitation on freedom of expression that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms would permit). Or, better still, they can fight the speech that they don’t like with their own better speech; after all, unlike most Canadian, they have unfettered access to the media—they are the media. What they cannot and should not do is enter into agreements that allows them, by virtue of their control of the most important media outlets, bypass the political process, impose their own wishes, and make their own wishes effectively the law of the land.

Competition between media outlets is important not only because it keeps prices down, and (generally) keeps quality up. Competition between media outlets is also essential to democracy, because, in the oft-quoted words of Justice Holmes, “the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas -- that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market...”

Defenders of freedom of expression should be alarmed not only when the Government seeks to enact laws that restrict speech or compel speech, but also when instead of competing in the market of ideas, the major media outlets decide together which speech will be heard and which suppressed. Even if the latter is annoying.